Aby Warburg’s Endless Album of Symptoms

Art History’s Fragmented Ghost

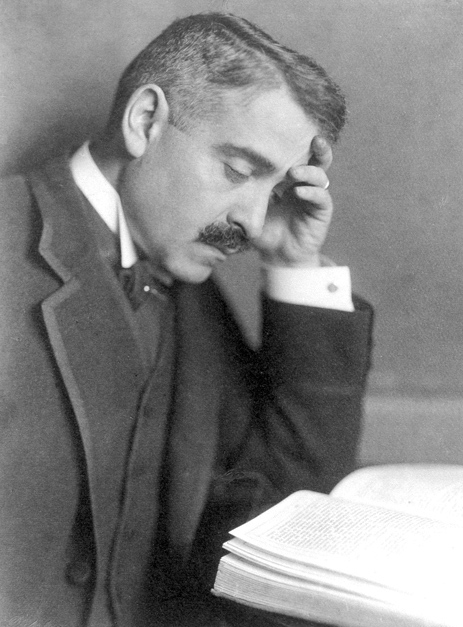

Aby Warburg (1866 - 1929) is a ghost haunting the discipline of art history, according to French philosopher and art historian Georges Didi-Huberman (1). Considered a ‘founding-father’ (2) of modern iconology, Warburg sought to integrate art history within the cultural sciences (3), working interdisciplinarily to challenge the aestheticized focus that dominated the field in the 1800s and establish art history as an anthropology or cultural science (Kulturwissenschaft). Warburg’s work has been less known in the English-speaking world, with iconology becoming associated with his student/colleague Erwin Panofsky (1892 - 1968) who further developed and popularized the method in the USA in the 1950s and 60s, without initially crediting Warburg’s influence (4), Panofsky’s 3-step iconographic method dominated art historical practice for decades, especially in English-speaking countries (5), and according to Didi-Huberman, ‘eclips[ed] Warburg [with writing that was] much clearer and more distinct, so much more systematic and reassuring” (6), as well as “more voluminous” (7). Warburg’s work was largely inaccessible to the English-speaking world, with few of his ‘ground-breaking’ writings translated into English until the end of the 20th century (8).

Following Didi-Huberman, Warburg is a ghost of art history, partially due to how difficult his work is to find and grasp, being spread out over so many unpublished manuscripts and documents (9). Didi-Huberman’s book, The Surviving Image: Phantoms of Time and Time of Phantoms; Aby Warburg's History of Art, was researched and written throughout the 1990s and published in French in 2002, and sought out and extensively referenced such unpublished documents in the Warburg Archive and in the Warburg Institute in London (10), where the research collections of Warburg’s Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek (KWB) was relocated in 1933 following the rise of Nazism in Germany.

Among these migrating fragments of art history’s past, Didi-Huberman sought to rediscover and examine Warburg’s ghostly legacy, particularly the psychological context of the foundational art historian’s investigations into psycho-cultural history. Not only Warburg’s dispersed and fragmentary legacy makes him a ghostly haunting, as Didi-Huberman points out, but also due to his primary biographer, Ernst Gombrich, who had “deliberately self-censor[ed] certain psychological aspects of Warburg’s life and personality” (11) in the 1970 publication that became the standard biographical source and reference (12).

In the final decade before Warburg’s death in 1929, his mental health deteriorated enough to require periods of institutionalization, and on his death he left theoretical ideas unresolved and unpublished, along with the monumentally ambitious and unfinished summary of his life’s work: the Mnemosyne Atlas. Far from seeing the fragmentary and unfinished nature of these artefacts, nor their psychological volatility, as something to censor and disregard in interpreting Warburg’s intellectual merit and theoretical conceptions, Didi-Huberman finds great merit and coherence in them, through a complex and extensive analysis.

In the concluding section of Didi-Huberman’s book, entitled “The Montage Mnemosyne: Pictures, Missiles, Details, Intervals”, he examines Warburg’s ‘style of thinking’, seen in these scattered notes and the provisionally arranged pictorial montages of the Atlas. In analysing these artifacts, and via extensive philosophical and poetical contemplation, Didi-Huberman presents an interpretation of Warburg’s psychological states as integral to his theoretical insights; the Mnemosyne Atlas as a project, whose provisional and unfinished nature is inseparable from its function as an innovative epistemological tool, and the challenges that Warburg’s original vision of iconology pose for art historical practice.

Reading Didi-Huberman’s Hurricane

Before discussing the ideas of Didi-Huberman, it is prudent to reflect on what the experience is of reading Didi-Huberman: for me, it is something like entering the dense, complex eye of a hurricane, a poetic montage of historic information analysed through intricate webs of specific, precise, and impassioned philosophical thoughts, reflections, and argumentations. In this rather meta-text, art historian Didi-Huberman is looking through the historical fragments of texts and images from Warburg, his predecessor in the history of art historical practice. According to Didi-Huberman, it was Warburg’s habit to “set forth multiple hypothesis [...] without ever providing a systematic way of unifying them, or even a way of provisionally toning down their contradictions” (13). Not unlike the subject of his study, Didi-Huberman “does not find it unsound to bring together thinkers who adopted mutually incompatible theoretical frameworks and who wrote in vastly different contexts. Such an approach avoids philosophical rigidity or dogmatism in favour of making connections on a broad array of topics. Didi-Huberman has no problem with comparing Warburg to Freud or with retaining the notion of ‘dialectics’ while using Foucault and Deleuze, who both explicitly rejected thinking in terms of dialectics” (14). The Surviving Image is a densely footnoted, often tangential and detailed discussion that loops back over reiterations and variations on the same expansive group of concepts. It is a text that absorbs itself in poetic contemplations of published and unpublished texts, letters, images, and research activities carried out by Warburg, his peers, his family, and his psychotherapist in the 1920s. Furthermore, Didi-Huberman pulls in texts, words and concepts from writers and philosophers from Warburg’s milieu and beyond such as Nietzsche, Goethe, Voltaire, Baudelaire, Foucault, Deleuze, and Merleau-Ponty. Meandering through space and time (in the non-linear space and time of memory), his writing is in conversation with his contemporaries in the current contestations and interpretations of Warburg’s biographical and intellectual legacy, while articulating his own individual understanding of vocabularies and philosophy relating images, time, and psychology, articulated across his own prolific publication history.

Warburg’s Pathos and Pathology

In developing a psychological portrait of Warburg’s ‘style of thinking’ and psychology during the last years of his life and work, Didi-Huberman does not shy away from revealing his failures, gaps, and incompletions, but rather collects and examines them. Warburg was a researcher, whose work investigated the “memorative function of images for human culture” (15), and the Mnemosyne Atlas, an “autobiographical quest” named after the classic Greek personification of memory, the atlas instigated as memory aid in an attempt to revive his research after his “fall into madness” (16). Among Warburg’s failings noted by Didi-Huberman was as an art historian incapable of remembering and recounting history as a linear and sequential story. Another was his failure to ‘schematize the history of images’ in 1905 and 1911 within regularly arranged tables, which Didi-Huberman demonstrated with the image of hand-drawn comparative tables of Pathosformeln, the boxes all left empty (17). These empty boxes and failures are one side of the extremes which Didi-Huberman observes in the notes and manuscripts created by Warburg in his last few years of life, in which he identifies a textual layout “corresponding exactly” with the visual layout of the Atlas: “by turns chaotic and ordered, compact and centrifugal, saturated and dispersed (…)” (18). In these rhythms of layout, Didi-Huberman looks past the “disappointment experience” of reading the manuscripts in any hope of “find[ing] in them a clearly formulated theoretical framework,” and instead finds their merit and “coherence in [their] style of exposition” (19).

In these layouts and notes, Didi-Huberman sees the rhythms of Warburg’s (manic/bipolar) style of thinking echoed in the title of one of Warburg’s final (1929) manuscripts, ‘Fugitive Notes’. The ‘explosive style of thinking’ (expanded upon via different meanings of the German words ‘flüchtig’ used by Warburg, and ‘fusée’ (‘rocket’) in Didi-Huberman’s original French) in these “hastily jotted” notes, in which “ideas burst forth but [...] also flee,” Didi-Huberman recognises a “twofold state [that] offers a good summary of Warburg’s whole way of thinking [...] at the time he was trying to elaborate the Mnemosyne Atlas” (20). Didi-Huberman also finds elaboration on this ‘style of thought’ in the publications and letters of Binswinger, Warburg’s psychotherapist. He claims that Binswinger’s book Über Ideenflucht (On the Flight of Ideas) describes the extreme, shifting cognitive tempo of the ‘maniacal style’ of mind, jumping from thought to thought rapidly and repetitively, and matches rhythms that he notes in Warburg’s manuscripts (21). Yet, Didi-Huberman emphasizes the genius insights that Binswinger’s maniac can access, with the examples of Nietzsche and Goethe.

In a 1927 presentation of an ‘intellectual autobiography’, Warburg himself reflected on the “dialectics of contradiction and intrication that governed his style of knowing things [... also] governed the objects of his knowledge” (22). He was aware that his intellectual practice was motivated by contradictions and struggle in his life: within himself, his orthodox family and cultural background (23), as well as in the discipline of art history he was attempting to change. He felt the threat of overwhelm, and of losing his sense of self.

For Didi-Huberman, Warburg’s emotional life and psychological struggles were inseparable from his work, an “oeuvre in which the dimension of pathos, indeed the pathological, proved to be essential” to the objects of his study (images as bearers of historical survivals) as much as on his “view that was brought to bear on them” (24). To understand Didi-Huberman’s interpretations of the dynamics of pathos (emotion) and the pathological in Warburg, we will need to consider the theories of Sigmund Freud.

Symptom Images of The Mad Scholar and Scientist of the Mad

According to Didi-Huberman, “the ‘mad’ scholar (Warburg) and the scientist of the ‘mad’ (Freud) were advancing along the very same terrain [...] of the ‘drama of the soul[.]’” (25) Freud’s theory of symptom formation, and his conceptual frameworks for the psychological processes of dreams (which he considers a special kind of symptom), are crucial to understanding how Didi-Huberman describes the function of images in his book The Surviving Image. Freud’s theories and vocabulary have influenced Didi-Huberman’s work as much as has Warburg himself (26), The Surviving Image being conceived of as one of two sequels (27) to Confronting Images: Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art, in which he presented his symptomatic approach to the analysis of images.

As part of the process of psychotherapeutic treatment developed by Freud, a therapist analyses the content of their patients’ dreams, which he famously called the “royal road to the unconscious”. Symptoms are understood to emerge as the result of a struggle between conflicting forces: the conscious mind (censor) and the unconscious mind, a repository of memory and desire (28). These products of psychological compromise can appear in such forms as slips-of-the-tongue, neuroses, accidents, and forgetting (29), but especially in the vivid and often visual-pictorial form of dreams, structured as a rebus (picture puzzle).

Didi-Huberman adapts Freud’s vocabulary and concepts of the symptom formation process to examine how images function in the world beyond dreams, and Freud’s ‘dreamwork’ (the four ways by which psychological material is converted into dream content, including ‘displacement’ and ‘pictorial arrangement’) (30). According to Didi-Huberman, images consist “of a mixture of rationality and irrationality” (31), and are “the most authentically symptomatic” when they “are most intensely contradictory” (32). In the “insane overdetermination of images” (33), he refers to the Freudian symptom’s quality (and therefore the image-symptom’s quality) of having a multiplicity of causes from activities of the unconscious.

Didi-Huberman claims that “no one besides Warburg, either before or after him, has ever understood so profoundly the efficacy of the process by which a symptom is revealed through the intensity generated by a displacement. Of all his contemporaries, only Freud [...] produced similar analyses of unconscious formations, dreams, fantasies, and symptoms” (34). This is to suggest that Freud and Warburg, despite their different fields and objects of study, were in fact uncovering the same psychological forces of humanity. Therefore it makes sense to seek greater clarity about the theoretical concepts and principles Warburg explored, such as the Nachleben and Pathosformel, using Freud’s ‘symptom formation’ as an interpretive device. Didi-Huberman suggests that this helps us “to clarify, and even to develop and to unfold, the temporal, corporal, and semiotic models Warburg employed” (35).

Nachleben, or The Afterlife of Images

One of the key concepts developed throughout Warburg’s work is that of ‘Nachleben’, or the afterlife of images. His work observed the ways in which certain fundamental patterns of emotional/expressive forms (Pathosformel) will disappear and reappear – survive – across long gaps and spans of human history, as seen in figurative art artifacts (images). Didi-Huberman, considering Warburg’s studies of human expression in artworks to actually be a study of symptoms, claims that for Warburg, expression “is not the reflection of an intention: it is, rather, the return in the image of something that has been repressed” (36).

The surviving images in art history appear like unsuccessfully repressed symptoms, memories from the unconscious that emerge as a compromise between the clashing forces in the human psyche. They are transformed through the dreamwork processes at work in the psyche of the artist/society, with the strangeness, ambiguities, or other alterations of the dreamwork. In the final chapter of The Surviving Image, appropriately titled “The Image as Symptom”, Didi-Huberman suggests that Warburg’s concept of Pathosformel should be understood “in terms of psychological symptomatology. The ‘emotive formulas’ are the visible symptoms – bodily, gestural, explicitly presented, figured – of a psychological time irreducible to the simple schema of rhetorical, sentimental, or individual vicissitudes” (37).

Didi-Huberman claims that Warburg found insights into the psychological dynamics of the unconscious memory workings of image survivals, following the psychological experiences and insights he gained during his institutionalization and psychotherapeutic treatment. In the manic ‘style-of-thought’ theorized by Bingswinger, and Warburg’s visual and textual layouts swinging between depressive sparseness and manic proliferation (38), Didi-Huberman argues that “Warburg’s whole way of thinking – its power and its tragedy – can be seen as revolving around this question of intervals. In working his way through the innumerable polarities waiting to be discovered in the details of the images he studied, he finally understood the ‘schizophrenia’ of Western culture in its entirety, with its perpetual oscillation” (39) between the manic and the depressive.

The Mnemosyne Atlas

Upon his return from institutionalization, Warburg “devoted the whole last period of his life to exhibiting pictures of his thinking” (40) in the form of the Mnemosyne Atlas. Despite the ‘depressive sparseness’ of his texts and manuscripts from this period, it is the monumental (and monumentally unfinished) Mnemosyne Atlas that displayed Warburg’s ‘manic proliferation’.

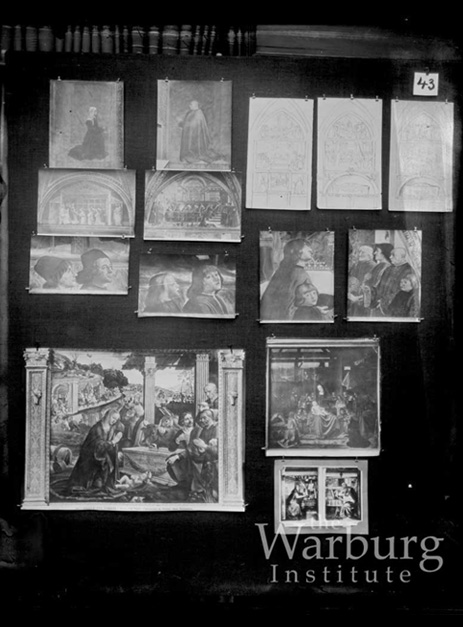

The Mnemosyne Atlas is a vast assemblage of images, a ‘photographic apparatus’ of prints from Warburg’s research collections, attached onto large black cloth frames with clips so that Warburg could rearrange them at will. Throughout Didi-Huberman’s discussion of the atlas, he utilizes photographs revealing the arrangements of this photographic apparatus: first with two photographs of early iterations taken in the context of the Kunstwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg in Hamburg in 1926-7 and 1927, in which black rectangular frames display groupings and series of small black and white photographic images, their content barely discernible, with the frames mounted along the reading room bookshelves; then two historic photographs taken of later, individual provisional plate arrangements – photographs of arrangements of photographs – featuring the entire black frame and the layout of individual black and white photographs can be observed again their black cloth backgrounds. The content within the selected and arranged photos displayed on these two plates can be discerned, but not in isolation, emphasizing their context and layout in relation to one.

Didi-Huberman contemplates how to approach this “paradoxical,” “irredeemably provisional” and “hypothetical work” (41), the arrangements and sequences of thousands of photos, for which Warburg never found a final form before his death, remain without an explicit version and interpretive guide in his notes and parallel provisional manuscripts. The individual photographs vary dramatically in scale, material and scope, of the art objects, scenes, details and motifs that they depict, with elements from across different places and times, with the ‘common denominator […] of the photographic scale’, allowing Warburg to experimentally arrange these radically diverse black and white images “in accord with his hypotheses” (42).

Much as Didi-Huberman found coherence in the style of exposition of Warburg’s scattered notes, he finds here the ‘coherence of his gesture [...] in the permutability itself[,]” (43) in endlessly changing transformations and configurations which Warburg would photograph and dismantle. Didi-Huberman observes that it is unclear how Warburg wanted others to look at and decipher the Atlas, with the dense intricate relationships between assembled images left uncertain (44). He suggests that the Atlas is a “kind of self-portrait […] burst into a thousand pieces” (45), and an atlas of the symptom (both of Warburg himself, and of images as symptoms that Warburg never could successfully categorize.) But “how to orient amid the unreason of the symptom?” (46).

Didi-Huberman understands the Mnemosyne Atlas as an experimental protocol of montage, where different variations of image combinations can be tested, and the complex specificities of each instance can be respected, not reduced into a unity. In comparing a plate of Warburg’s Atlas to an image from an 1887 German ethnographic atlas, Didi-Huberman sees the other atlas creating a sense of continuity across cultures and times in the Cosmological imagery it depicts with uniform line drawings. In Warburg’s Atlas, on the other hand, Didi-Huberman observes that the photographic images emphasize the differences and singularities of the appearances of Cosmological imagery from varying artifacts, where the individual details retain their complex specificity despite the common forms seen to survive across them. He also argues against a model for the Mnemosyne Atlas in most of the artistic and avant-garde experiments occuring around the same time he created it. Didi-Huberman does consider the atlas to be an avant-garde object, not in “making a break with the past, [... but in making] a break with a certain way of thinking about the past” (47).

Didi-Huberman finds a model for the Mnemosyne Atlas in the “structure of the objects it analytically investigates”, with an example in a photograph of the Italian Renaissance frescoes in Sassetti Chapel in Florence by Domenico Ghirlandaio. Details of this chapel are disassembled and reassembled by Warburg in his Plate 43, where he compares in polarities or across sequences the different combinations of ancient and contemporary influences, North and South European styles, pagan and Christian sensibilities, and depictions of past, present and future, locations both near (Florence) and far (Bethlehem), all montaged within frescos across the surfaces of the chaple’s pictorial ensemble. Through selecting and displaying aspects of the chapel in dialogue with one another on the black screen of the Plate, Warburg’s montage reveals Ghirlandaio’s paintings to also be arrangements of montages of space and time. The artwork, as a form of memory, functions like dream images, the rebus pictorial puzzle, which symptomatically reveal the compromises made unconsciously by the artist, between the contradictions of conflicting cultural forces, including ancient pagan imagery persisting amid Christianity.

Warburg’s Inexhaustible Art History

Didi-Huberman presents a re-analysis of Aby Warburg’s legacy as a challenge and revision to the practices of art history to which he is considered a founding father. He considers the Mnemosyne Atlas as being an innovative epistemological tool for art history, utilising a new form of photographic montage with which Warburg made perceptible into endlessly proliferating intrications and (symptomatic) overdeterminations at work in the history of images (48). He esteems it as an innovation that builds upon the past and the expository structure of art history lectures and slides, so that he could present and contemplate the dialectic between images from different times and places, not in a linear narrative sequence, but being able to ‘jump’ across time with the temporal and spatial juxtapositions characteristic to memory.

However, the symptomatic conception of art history, which Didi-Huberman perceives Warburg to be investigating with this epistemological tool, is not the ‘Iconology’ as it is currently understood. According to Didi-Huberman, contemporary iconology “is not the ‘science without a name’ that […] Warburg was hoping to create” (49), but “only constitutes one instrument among others” because, as Didi-Huberman argues, Panofsky “secretly rid [iconology] of all the great theoretical challenges that Warburg’s oeuvre had borne” (50).

He contrasts Panofsky’s ‘standard iconography’ with what he considers to be Warburg’s original vision for iconology, one which he dismisses as reductive. He sees Panofsky’s ‘decodings’ of images to be a reduction of “particular symptoms to the symbols which encompassed them in a structure”, seeking to separate form from content, and insisting upon the certainty of ‘iconographic discernment’. In contrast, he claims that Warburg “never stopped decomposing this kind of discernment or discrimination in order to work on the basis of intrications”, which Didi-Huberman names the “iconographic indiscernibles” (51). The complex, mysterious, and intertwining dynamics, which result in the image-symptom formation, is what is being investigated. When Didi-Huberman explains Warburg’s use of details in the Atlas based on the detail’s symptomatic nature, he insists that the identity or identification of the figure is not the goal of this (Freudian, psychoanalytical) investigation (52). Didi-Huberman argues that, for Panofsky, in order to study something one must know for certain what it is – for example, whether a figure represents “Judith OR ELSE Salome”. For Warburg it is instead “Judith WITH Salome and with so many other possible incarnations”. According to Didi-Huberman, Warburg did not want to solve and decode the pictorial riddle (rebus), which is the “declared aim of standard iconography” (53). Instead, Warburg wanted to produce the rebus itself – to unfold its complexity rather than reduce it” (54). This unfolding of complexity, the revealing and exploring of it, is the work of the Mnemosyne Atlas.

Finally, Didi-Huberman considers Warburg’s work as calling art historians to this maddening use of ‘non-knowledge’ and endless, subjective interpretation, and in which the scholar is as personally and psychologically intertwined and intricated as the objects of his/her study. This ‘emotional’ or ‘even psychopathological’ model (55) used by Warburg (and Didi-Huberman) is endless, inexhaustible (and exhausting), like the interminable analysis Freud ‘later [...] resorted to” (56). Didi-Huberman judges “the ambition of Warburg’s ‘science without a name’ by the yardstick of its own incompleteness” (57). That incompleteness finds new meaning for art history, when seen as the gaps or intervals of time and space that structure the symptom and the symptom image.

Sarah Hermanutz studies Media Environments with Ursula Damm at the Bauhaus University Weimar and is based in Berlin. She is developing her thesis project The Pathetic Sublime, drawing inspiration from Warburg’s cognitive montage strategies as well as Didi-Huberman’s insights into the Image-As-Symptom.

sarahhermanutz.com

Where to see more of the Mnemosyne Atlas:

The historic photographs of the provisional Atlas panels from 1928 and 1929 can be viewed online courtesy of the The Warburg Institute at the University of London.

https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/library-collections/warburg-institute-archive/online-bilderatlas-mnemosyne

The Mnemosyne Atlas was recreated from the original archive material and publicly exhibited in 2016 at the ZKM in Karlsruhe, for the 150th Anniversary of Aby Warburg’s birth. It was curated by Roberto Ohrt and Axel Heil in cooperation with The Warburg Institute.

https://zkm.de/en/event/2016/09/aby-warburg-mnemosyne-bilderatlas

In Sept-Nov 2020, the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in Berlin will exhibit this recreation of the original Atlas, with a conference and public program presented online due to Covid-19.

https://www.hkw.de/en/programm/projekte/2020/aby_warburg/bilderatlas_mnemosyne_start.php

Concurrently in Aug - Nov 2020 the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin will present original artworks from the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, which were represented in Warburg’s image research collections, in Between Cosmos and Pathos: Berlin Works from Aby Warburg's Mnemosyne Atlas.

https://www.smb.museum/en/exhibitions/detail/between-cosmos-and-pathos/

Bibliography

Alloa, Emmanuel. “Iconic Turn: A Plea for Three Turns of the Screw.” Culture, Theory and Critique 57, no 2 (July 2016): 228-250.

De Cauwer, Stijn, and Laura Katherine Smith. “Editorial Introduction.” In “Critical Image Configurations: The Work of Georges Didi-Huberman.” Special issue, Angelaki 23, no 4 (August 2018): 3-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969725X.2018.1497264 .

Diers, Michael, Thomas Girst, and Dorothea Von Moltke. “Warburg and the Warburgian Tradition of Cultural History.” New German Critique, no 65 (Spring-Summer 1995): 59-73.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. The Surviving Image: Phantoms of Time and Time of Phantoms; Aby Warburg's History of Art. Translated by Harvey Mendelsohn. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017.

Freud, Sigmund. The Freud Reader, edited by Peter Gay. New York: W. W. Norton, 1989. Norton paperback edition reissued, 1995. Page references are to the 1995 edition.

Müller, Marion G. "Iconography and Iconology as a Visual Method and Approach." In The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods, edited by Eric Margolis and Luc Pauwels, 283-297. London: Sage Publications, 2011.

Rampley, Matthew. "Iconology of the Interval: Aby Warburg’s Legacy." Word and Image 17, no 4 (2001): 303-324. https://doi.org/10.1080/02666286.2001.10435723

Endnotes

1. Georges Didi-Huberman, The Surviving Image: Phantoms of Time and Time of Phantoms; Aby Warburg's History of Art, trans. Harvey Mendelsohn (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017), 16.

2. Marion G. Müller, “Iconography and Iconology as a Visual Method and Approach,” in The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods, ed. Eric Margolis and Luc Pauwels (London: Sage Publications, 2011), 284.

3. Michael Diers, Thomas Girst, and Dorothea Von Moltke, “Warburg and the Warburgian Tradition of Cultural History,” New German Critique no. 65 (Spring-Summer 1995): 72. www.jstor.org/stable/488533.

4. Müller, “Iconography and Iconology,” 283.

5. Ibid. 288.

6. Didi-Huberman, The Surviving Image, 14.

7. Matthew Rampley, “Iconology of the Interval: Aby Warburg’s Legacy,” Word and Image 17, no. 4 (2001): 303. doi.org/10.1080/02666286.2001.10435723.

8. Rampley, “Iconology of the Interval,” 303.

9. Didi-Huberman, The Surviving Image, 14.

10. Ibid. iv.

11. Ibid. 14.

12. Diers, Girst, and Von Moltke, “Warburg and the Warburgian Tradition”, 65.

13. Didi-Huberman, The Surviving Image, 121.

14. Stijn De Cauwer and Laura Katherine Smith, “Editorial Introduction,” in “Critical Image Configurations: The Work of Georges Didi-Huberman,” Special Issue, Angelaki 23, no. 4 (August 2018): 5. doi.org/10.1080/0969725X.2018.1497264.

15. Didi-Huberman, The Surviving Image, 302.

16. Ibid. 296.

17. Ibid. 303.

18. Ibid. 304.

19. Ibid. 305.

20. Ibid. 306.

21. Ibid. 308.

22. Ibid. 310.

23. Ibid. 309.

24. Ibid. 14.

25. Ibid. 333.

26. Stijn De Cauwer and Laura Katherine Smith, “Editorial Introduction,” in “Critical Image Configurations: The Work of Georges Didi-Huberman,” Special Issue, Angelaki 23, no. 4 (August 2018): 4.

27. Didi-Huberman, The Surviving Image, iv.

28. Sigmund Freud, The Freud Reader, ed. Peter Gay (New York: W. W. Norton, 1989; 1995), 28. Citations refer to the 1995 edition.

29. Sigmund Freud, The Freud Reader, 163.

30. Sigmund Freud, The Freud Reader, 161.

31. Didi-Huberman, The Surviving Image, 303.

32. Didi-Humberman, Confronting Images: Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art, 262.

33. Didi-Huberman, The Surviving Image, 20.

34. Ibid. 154.

35. Ibid. 175.

36. Ibid. 180.

37. Ibid. 180.

38. Ibid. 333.

39. Ibid. 330.

40. Ibid. 300.

41. Ibid. 295.

42. Ibid. 298.

43. Ibid. 301.

44. Ibid. 304.

45. Ibid. 302.

46. Ibid. 303.

47. Ibid. 317.

48. Ibid. 299.

49. Ibid. 324.

50. Ibid. 325.

51. Ibid. 325.

52. Ibid. 322.

53. Ibid. 325.

54. Ibid. 326.

55. Ibid. 323.

56. Ibid. 333.

57. Ibid. 175.