A Critical Review of the Essay “What Do Pictures Want?” by W.J.T Mitchell: On the Subaltern Model of the Picture

Introduction: ‘The subaltern model of the picture’

The essay “What Do Pictures Want?” is the second chapter of the book What Do Pictures Want: The Lives and Loves of Images, a collection of essays by William John Thomas Mitchell, published by the University of Chicago Press in 2005. This essay suggests an academically unconventional perspective on visual culture, which the author calls ‘the subaltern model of the picture’ (p. 34). This approach invites the pictures themselves to speak, and represents – as opposed to focusing on the message pictures communicate or the effect they produce on others – an open ended invitation for the viewers to reflect on their own position in relation to pictures. In the following, Mitchell’s main arguments and thesis statements will be discussed, which lead to his key concept of the subaltern view on pictures, structured into: ‘the downcast other’, ‘images as women’, pictorial power, pictorial desire and the negation of pictorial desire. In regards to each key statement and concept, it will be shown how the author refers to other theorists and well-known imagery to drive his arguments and claims further.

Mitchell starts with the question ‘What do pictures want?’ “as a kind of thought experiment, simply to see what happens” (p. 30). He is also convinced that this is a question viewers inevitably ask themselves when looking at images. The question is an invitation to the reader to undermine ready-made models of interpretation and instead reframe one’s relation to pictures in what Mitchell hopes will result in “a slight modification” of the interpretation of images (p. 46). On a fundamental level, Mitchell thus questions the conventional ideology of how we encounter images. In the academic world, he is well known for his specific approach to Image Science and Visual Culture with a marked contemporary view (i.e. popular culture) and against the backdrop of current social and political issues, such as racial problems, when casting images as marginalised people (p. 35). By giving images their own voices, he proposes a specific anthropological view on pictures. Thus, his approach is not primarily to contextualise as an art historian, but rather to approach pictures as part of everyday ways of seeing.

‘The Personhood of Pictures’

The foundational concept that serves as the base for discussion in the essay is the ‘personhood of pictures’(p. 32). This concept is key, because, to make sense of the question ‘What do pictures want?’, the author sets up the premise that pictures are animated beings that can even have an own want. To support this thesis, he gives a plethora of references seeking to demonstrate how one can – and already does – consider pictures to be living things. In a respective reference, Mitchell refers to Marx and Freud, who both dealt with ‘the personhood of things’ and defined it as the tendency to assign a living character to nonliving objects (p. 30). Mitchell adds that images and pictures are particularly such ‘things’ subject to being assigned ‘personhood’ since they often exhibit human figures and faces. However, as opposed to Freud, Mitchell does not claim that one has to be cured from “[one’s] magical, premodern attitude toward objects, especially pictures” (p. 30). Instead, the author insists that one needs “to understand them, to work through their symptomatology” (p. 30). Thus, Mitchell makes an effort to work through this symptomatology by trying to approach pictures as if they had a will and agency of their own. He states: “It’s crucial to this strategic shift that we not confuse the desire of the picture with the desire of the artist, the beholder, or even the figure in the picture” (p. 46). Following in the footsteps of two of the greatest historic thinkers to support his argument and to legitimise his question, Mitchell moves on to more commonplace, everyday perceptions of “the personified and ‘living’ work of art” (p. 31). For this, the author refers to the discipline of art history, whose representatives do know that pictures are only material objects, but talk about them as if they “had feeling, will, consciousness, agency, and desire” (p. 31). The personified image is also illustrated with another example: The hesitation everyone feels to deface a picture of one’s mother. As summarising argument for the prevalence of animism of pictures, Mitchell notes that the reigning cliché of contemporary visual culture is that images have a psychological or social power of their own. This can be noticeably witnessed in advertising, where certain images are said to be more influential than others; “as if they had an intelligence and purposiveness of their own” (p. 31).

‘The Subaltern Downcast Other’

A second concept that structures Mitchell’s line of argumentation is the idea of the picture as a subaltern, ‘downcast Other’ (p. 29). Here, he draws a parallel between people of colour, women and pictures. He argues that they all have to struggle hard to be heard and are not allowed to speak for themselves: “The question [ What do pictures want?] echoes the whole investigation into the desire of the abject or downcast Other, the minority of the subaltern” (p. 29). This approach is summarised in what he calls ‘the model of the subaltern’. The parallels he draws between these marginalised groups is part of his specific anthropomorphic perspective to view pictures as living things. Here, Mitchell makes use of a myriad of references to support this rather controversial claim. Most prominently, he makes the bold statement that pictures are principally all female, conceiving of ‘images as women’: “As for the gender of pictures, it’s clear that the “default” position of images is feminine, “constructing spectatorship,” in art historian Norman Bryson’s words, “around an opposition between woman as image and man as the bearer of the look” – not images of women, but images as women (p. 35).”

As with most other thesis statements, Mitchell’s claim again is in direct correlation with Norman Bryson, another art theorist and historian, for not leaving such a statement theoretically unsupported. Mitchell seems to be very intent on legitimising and academically securing any argument he makes. In a next logical step, Mitchell claims that “the question of what pictures want, then, is inseparable from the question of what women want” (p. 35). According to him, what pictures want should be modelled on the desire of women. As direct result of this causality, Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Wife of Bath’s Tale is introjected into the essay to offer a possible answer on the desire of women – and with it, on images. In this tale, a knight, who raped a lady of the court is given one year reprieve on his death sentence to go on a quest for the right answer to ‘What is it that women most desire?’. The ultimate answer of this quest is that women want what they lacked: power. This insight is then directly transferred to pictures, stating “above all they would want a kind of mastery over the beholder” (p. 36). Regarding this thesis, the additional proof introduced by Mitchell is the concept of ‘the medusa effect’, which characterises another possible interaction between the viewer and the viewed (p. 36). This effect describes the moment, when a person who is looking at a picture is frozen, spellbound by it. Strategically, such ‘medusa effect’ is interpreted by Mitchell as a further confirmation that images are female as both pictures and women can hold spellbinding power over a beholder: “This effect is perhaps the clearest demonstration we have that the power of pictures and of women is modeled on one another, and that this is a model of both pictures and women that is abject, mutilated, and castrated. The power they want is manifested as lack, not as possession” (p. 36).

According to Mitchell, ‘the medusa effect’ even holds a second implication, which is the picture’s desire to change positions with the viewer: “The paintings’ desire, in short, is to change places with the beholder, to transfix or paralyse the beholder, turning him or her into an image for the gaze of the picture” (p. 36). While the thesis of ‘images as woman’ might speak more on the issue of pictorial desire, ‘the actual dialectics of power’ in our relation to pictures is, according to Mitchel, even better illuminated, when casting pictures as marginalised people of colour (p. 34). The author writes: “If pictures are (real life) persons, then, they are colored or marked persons, and the scandal of the purely white or purely black canvas, the blank, unmarked surface, presents quite a different face” (p. 35). To give substance to this statement, Mitchell looks to Martin Jay, Franz Fanon and the practice of idolatry as it relates to racism. Franz Fanon was a French psychiatrist and political philosopher of colour, who wrote about the construction of the racial and racist stereotypes that are cast as a technique of domination. Racism renders its subject “simultaneously hyper visible and invisible, an object of, in Fanon’s words, ‘abomination’ and ‘adoration’” (p. 34). This claim also holds biblical references as: “Abomination and adoration are precisely the terms in which idolatry is excoriated in the Bible: it is because the idol is adored that it must be abominated by the iconophobe. The idol, like the blackman, is both despised and worshipped, reviled for being a nonentity, a slave, and feared as an alien and supernatural power” (34). With this interesting analogy that if pictures were persons, they would be similarly stigmatised as people of colour, Mitchell sensitises the reader towards the comparable unfair treatment of images (p. 46).

From Pictorial Power to Pictorial Desire

Included in Mitchell’s above mentioned ‘subaltern model of the picture’ as ‘the downcast Other’ is the understanding that pictures may be a lot weaker than we think. In contrast to the conventional view, correlating the power of images with the power of the interpreter, Mitchell seeks to suspend this belief by shifting one’s perspective from pictorial power to pictorial desire (p. 34). To this end, Mitchell questions the role of cultural critics such as himself: Is the critics’ role “to demystify these images, to smash the modern idols, (…) to discriminate between true and false?” (p. 32). One such commonplace practice of dealing with visual culture, which Mitchell questions, is to use criticism as a strategy of political intervention that aims to expose images as damaging agents of manipulation. In order to illuminate this claim, another widely known visual culture theory is used: ‘the male gaze’ (p. 32). The male gaze describes the pre-dominant heterosexual white male gaze, often portrayed, for example, in Hollywood cinema, that discriminates women as objects. A way of seeing that is said to manipulate the audience and subsequently society at large. A more extreme iteration of this is Catherine Mackinnon’s view on pornography: She sees pornography not just as a ‘representation’ of violence towards and degradation of women but as an actual, real act (p. 32). To her, the images themselves are agents of violence.

Regarding the above mentioned reigning perceptions on pictorial power, Mitchell concludes that the conventional type of political critique is too easy and ultimately ineffective, “because one can take a tough stand on them (i.e. pictures), and yet, at the end of the day, everything remains pretty much the same” (p. 33). Instead, Mitchell sees common political critique as “a kind of testimony to the incorrigible character of our tendency to personify and animate images,” and states (p. 33): “In any event, it may be time to rein in our notions of the political stakes in a critique of visual culture, and to scale down the rhetoric of the ‘power of images.’ (…) The problem is to refine and complicate our estimate of the power and the way it works. That is why I shift the question from what pictures do, to what they want, from power to desire, from the model of the dominant power to be opposed to the model of the subaltern to be interrogated or (better) to be invited to speak” (p. 33).

What Do these Pictures Want?

Once having fully established ‘the subaltern model of the picture’, Mitchell continues with a very practical analytical approach, applying the question ‘What do pictures want?’ to selected examples from popular culture. Thus, he wants to test “what happens if we question pictures about their desires instead of looking at them as vehicles of meaning and instruments of power” (p. 36). This approach allows one to look at the question from different angles and through different types of images. An endeavour Mitchell evaluates as follows: “I could have made this inquiry harder by looking at abstract paintings (pictures that want not to be pictures) or at genres such as landscape (…). But the question of desire may be addressed to any picture, and this chapter is nothing more than a suggestion to try it out for yourself” (pp. 46-47).

The artworks he looks at can be grouped into two main categories: First those that show a direct expression of pictorial desire; second, the negation of pictorial desire.

The Expression of Pictorial Desire

For the first category – the expression of pictorial desire to be identified by lack –, Mitchell uses an icon of American history: The Uncle Sam recruiting poster for the U.S Army, designed during World War I by James Montgomery Flagg. The picture’s obvious message (positive desire) can be read as a direct appeal or a demand, issued by the picture (i.e. I want You for U.S. army). Mitchell then attempts a deeper analysis by asking ‘What does this picture want in terms of lack?’, concluding: “What this (…) nation (i.e. and with it the picture) lacks is meat - bodies and blood - and what it sends to obtain them is a hollow man, a meat supplier” (p. 38). The direct message sent by the picture thus fully aligns with the pictures hidden desire and lack, however, the direct appeal predominates.

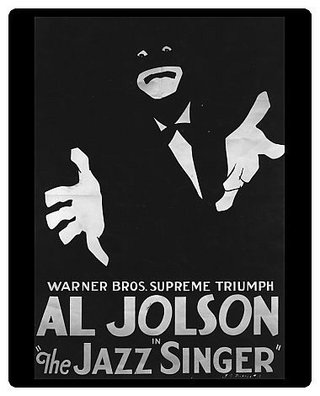

As an example where “sometimes the expression of a want signifies lack rather than the power to command or make demands”, Mitchell uses the Warner Brother’s promotional poster for the movie The Jazz Singer, which more closely ties in with the thesis of the ‘subaltern model of the picture’ (p. 38). This poster serves as an especially fitting example, as, similar to Mitchell’s approach of casting pictures as people of colour, a white performer is seen impersonating a person of colour with the technique of ‘black face’, a form of racial masquerade prevalent at the time. When looking beyond the obvious function of this advertising image, the seemingly straight forward desire, to lure people to the movie theatres, fades. Instead, an inquiry into the picture’s lack reveals “an impotence (…) - an invitation to see, feel, and speak beyond the veil of racial difference” (p. 39). What is striking about this image is that the outline of the figure is not visible as it blends completely with the black background. In a fetishisation of the racial masquerade, the figure is rather reduced to a fixation on the eyes, the mouth, the hands as “illuminated gateways between the invisible and visible man, inner whiteness and outer blackness” (p. 39). Mitchell sees in this a clear lack of the picture, because what the picture wants is a stable relationship between the figure and the background (p. 38). It desires precisely that which it cannot have, due to the stigmata of racism inscribed in it: Set boundaries between the body and space.

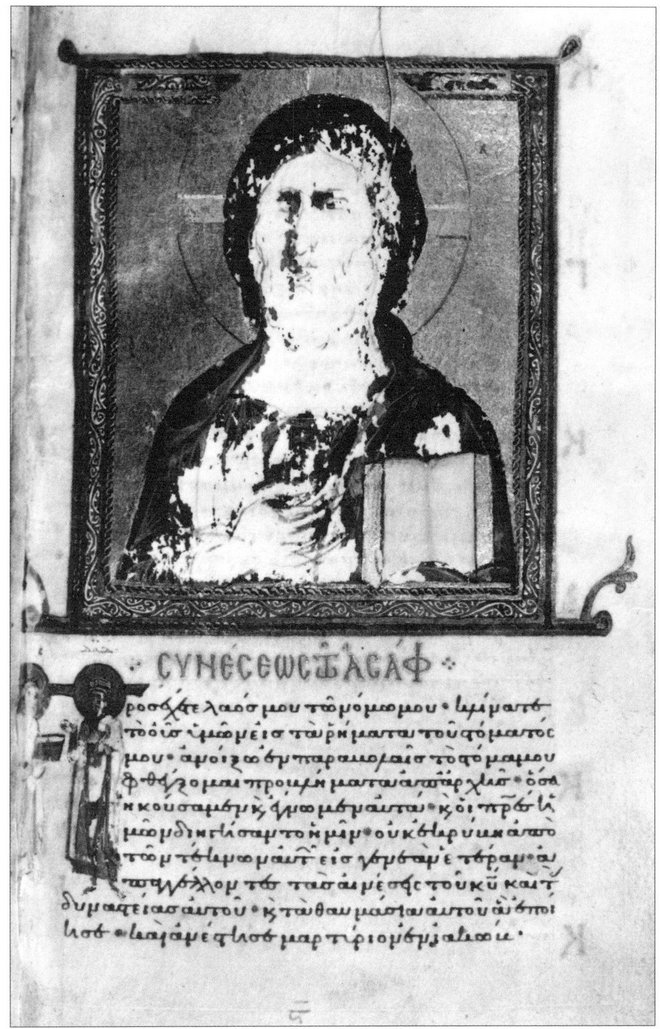

With another image example, that of a Byzantine miniature of the eleventh century, Mitchell further stretches the scope of the essay to include historical and religious interactions with images. Like the other examples, there first is a direct expression of the pictorial desire: “Give heed, O my people to my law; incline your ears to the words of my mouth” (p. 39). For orthodox believers, this depiction of the Icon of Christ is not a mere depiction but is perceived almost like a portal to the spirit of Christ. It is the incarnation of the holy spirit and because of this, generations of devoted believers felt compelled to embrace the image not just with their ears, but by kissing the figure. This religious practice around the artwork shows an extreme: Both, an animism inscribed to an inanimate depiction, and the perceived appeal/desire issued by the Icon. Because of this, the object of visual desire in the picture literally disappears and yet, it still holds a special significance and is nevertheless able to express a want, which gets an immediate behavioural response from the viewer. Regarding the first category (the expression of pictorial desire to be identified by lack), Mitchell summarises that: “These sorts of direct expressions of pictorial desire are, of course, generally associated with ‘vulgar’ modes of imaging - commercial advertising and political or religious propaganda” (p. 39). Notably, Mitchell visualises his point with exactly such examples taken from popular culture which are close to the reader, before moving on to more elitist artwork. This way of proceeding highlights Mitchell’s stance towards Visual Culture Studies as part of everyday ways of seeing, in an effort to broaden the discourse away from a pure contextualisation in art history and academia.

The Negation of Pictorial Desire

But what about works of art that do not serve a function, but are rather supposed to just ‘be’ (autonomously beautiful) (p. 39)? This question brings us to the second category: the negation of pictorial desire. Again, Mitchell makes use of observations by other expert voices as well as image analyses of prominent artworks to support his arguments. The first examples are drawn from the observations of art critic Michael Fried, who argues that the negation of direct signs of pictorial desire enabled the emergence of modern art (pp. 39-42). These types of images “get what they want by seeming not to want anything, by pretending that they have everything they need” (p. 42). They are characterised by the seeming indifference of the artwork towards the beholder and the artworks’ absorption in its own internal drama. Different from the previous examples, here it becomes easier to look past what the figures in the picture appear to want and to focus on other legible signs of desire they might convey. For example, in Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin’s painting Soap bubbles, the desire is described as contemplative and seen as correlating to the artist’s own fascination in the act of painting. The desire is visualised in a shimmering globe, which the figure in the painting is so intently focused on and which the artist suspects will equally absorb the beholder in front of the finished artwork. From this, one could conclude that the picture’s desire is to equally fascinate every party in a contemplative act.

Fried’s other example is Théodore Géricault’s Raft of Medusa. This painting could be seen as the violent and dark counterpart to the previous more serene image. The figures of this painting appear to be fully entrenched in their own internal drama: “The “strivings of the men on the raft” are not simply to be understood in relation to its internal composition and the sign of the rescue ship on the horizon, “but also by the need to escape our gaze, to put an end to being beheld by us, to be rescued from the ineluctable fact of a presence that threatens to theatricalise even their sufferings” (p. 44).

Here, one can discern another underlying general theme of Mitchell’s essay: The idea of mutual acknowledgement and reciprocal recognition between the beholder and the picture being beheld. In Mitchell’s dealing with Géricault’s painting, one can most vividly grasp Mitchell’s idea to create an encounter between the picture and the beholder: "They (i.e. the pictures) want a hermeneutic that would return to the opening gesture of art historian Erwin Panofsky’s iconology, before Panofsky elaborates his method of interpretation and compares the initial encounter with a picture to a meeting with “an acquaintance” who “greets me on the street by removing his hat” (p. 48).

Another image that speaks specifically to the phenomenon of being looked at is the photo collage by Barbara Kruger Your Gaze Hits the Side of My Face. It illustrates what is dubbed ‘the purist pictorial desire’ (44). This picture is defined by a strong contrast between the marble face in the picture and the visible typography. The face’s blank eyes and stony absence make it seem introspect. It appear beyond desire and oblivious to our gaze. However, the graphic typography placed on top of the portrait paints a different picture. With the words ‘Your Gaze Hits the Side of My Face’ the impression of the figure changes “as if it were a living person who had just been turned to stone, and the spectator were in the Medusa position, casting her violent, baleful gaze upon the picture” (44). Whether the picture wants or does not want to be seen remains unclear. Mitchell concludes – presumably due to the image-text interplay – that what the picture wants most is what it lacks: to be heard.

In order to bring the idea of negation of pictorial desire to an endpoint, Mitchell finally looks at modernist abstraction. He supports his own view by referring to theorist Wilhelm Worringer, who wrote about the negation of the beholder’s presence in his book Abstraction and Empathy (p. 44). An immediate visual example is found in Robert Rauschenberg’s White Painting, which shows a state of final reduction of pictorial desire: abstract pictures that do not want to be pictures (44). Rauschenberg ‘though still described even those surfaces as “hypersensitive membranes … registering the slightest phenomenon” (44). In other words, even here the pictorial ‘desire not to show desire’ is still a form of desire, an idea Mitchell draws from renowned French psychoanalyst Lacan (p. 44).

Mitchell thus proposes to the reader to take a position outside of the practices of conventional Image Science, because “contemporary discussions of visual culture often seem distracted by a rhetoric of innovation and modernization. They want to update art history by playing catch-up with text based disciplines and with the study of film and mass culture” (47). Instead, he argues that “this complex field of visual reciprocity is not merely a byproduct of social reality but actively constitutive of it. Vision is as important as language in mediating social relations, and it is not reducible to language, to the ‘sign’, or to discourse” (47). This can also be seen as yet another reason why Mitchell asks his guiding question ‘What do pictures want?’: to free pictures and imagery from the control of language. In order to achieve this, new discourses need to be invented, because ultimately “what pictures want from us, what we have failed to give them, is an idea of visuality adequate to their ontology” (47).

Concluding Review

In an overall assessment of the essay, one can say that Mitchell successfully provokes an unexpected change in one’s view on images. However, Mitchell’s perceived need to be infallible unfortunately compromises the comprehensibility of the text partially. For example, as already noted, Mitchell uses a myriad of references – in an endeavour he himself calls a “hasty survey” – to flag and support his statements, even to a degree where many statements become rather unclear than clearer (46). One striking case of this comes with the unexpected claim that if pictures where persons they would be people of colour, which is introduced through a puzzling mixture of quotes, concepts, name-dropping and even biblical references (34-35). This sometimes creates the impression that Mitchell prioritises the number of sources and references over their inherent persuasiveness. The sheer amount of references is overpowering, does not build an understandable hierarchy of messages and creates an unsorted impression, leaving the reader with the task of sifting through the examples in order to properly understand what their combined meaning is. More examples do not always guarantee one’s greater understanding, especially when some of these references require a specific pre-knowledge, not provided in the essay itself, for example orthodox beliefs and practices in regards to the Byzantium miniature, or the technique of ‘Black Face’ in regards to the Jazz Singer. It almost seems that Mitchell’s abundant use of references serves him as a ‘preemptive strike’ against potentially being called a non “modern, rational, secular person” (31). A hypothesis, which is also supported by the fact that he adds nine additional pages devoted to answering ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ at the end of his essay.

To conclude, with his essay and core thesis that pictures have an own intrinsic pictorial desire, Mitchell in the end achieves a noteworthy change of the reader’s relation to and interpretation of images. By casting images as ‘marginalised persons’, he draws an interesting analogy to unravel the established power dynamics towards pictures and thus opens up the space for the potential need of a new discourse. Let’s invite pictures to speak as opposed to just praise meaning over them and consciously always ask the question: ‘What does this picture want?’

This review focuses on many examples from art history to delve into the guiding question: What do pictures want? For a contemporary video artwork, dealing with related questions around ‘the personhood of pictures’ and pictorial desire, from a modern digital media perspective have a look here:

SKIN FLESCH BONES

von Kristin Jakubek

Klicken Sie auf den Play-Button, um externe Inhalte von Vimeo.com zu laden und anzuzeigen.

Externe Inhalte von Vimeo.com zukünftig automatisch laden und anzeigen (Sie können diese Einstellung jederzeit über unsere »Datenschutzerklärung« ändern.)

Video artwork - ‘SKIN FLESH BONES’, 2018, Kristin Jakubek