»Images and Words: What Do They Want from Us?«

In the first chapter of his book Ways of Seeing (1972), John Berger deals with topics such as our “way of seeing” the world through the image, how “seeing comes before words”, how it is more convincing than just reading something, how a creative product becomes art, what is “authenticity” and what makes some art products more valuable than others. He urges us to question what we see and how we react to it, depending on our habits and conventions.

The main argument of the text is to assess the relationship between the things we see and how we understand them by referring to our knowledge – unintentionally and sometimes intentionally. Images speak more powerfully than words or intentions. People can recreate their way of perceiving the world through images. Every image externalizes its creator’s ’way of seeing’. Reproduction, for instance, is a possible way to bring images into new contexts. Over the last century, with the invention of the camera and the printing press, reproduction has become the main aspect of the images we see. After providing a summary of Berger’s second chapter, I will relate his essay to my artistic work, with the focus on the concept of “reproduction” and the effect of sound.

Firstly, Berger analyses how we see images and how we make assumptions. Berger refers to this process of making assumptions and coming up with thoughts as “mystification”. He argues that when an image is presented as a work of art, the way people look at it is affected by a whole series of learned assumptions concerning the concepts of beauty, truth, genius, civilization, taste, etc. (1) All these presumptions influence the way we look at images as well as how we react to them both emotionally and analytically. Berger analyses various mystification types and the factors involved in them. One of these types is looking at an image that is related to a history of the past. The history behind the image almost always shifts the way we see it and changes the image’s context. The context of an image may be completely different from its history and the history of an image contributes to the context; therefore, it mystifies it. Berger describes this process as follows: “The past is never there waiting to be discovered, to be recognized for exactly what it is. History always constitutes the relation between a present and its past.” (2) This is of course directly related to our assumptions concerning the background of the past story we know about an image. Berger gives Frans Hals’s Regents of the Old Men’s Alms House as an example. First, we take a look at the paintings.

The paintings appear to be the portraits of some men and women, depicted in a dark, depressing environment. The people in the pictures have some sort of menacing look in their faces. We, as viewers, who are witnessing the past of this painting created in the 16th century, have already begun to mystify it based on our assumptions. These are some paintings by Frans Hals, who was, back than, more than eighty years old, poor and desperate to paint these images to receive three loads of peat. Otherwise, he would have frozen to death. Now, as viewers who know the past and the history behind these paintings, it is impossible to avoid the past. Berger quotes Seymour Slive’s study on Frans Hals and comments on how the paintings worked on him to alter his opinions. He almost omits the fact that Hals was a poor guy who painted the people who provided food and shelter to him, instead Seymour mentions a seduction we feel when he looks at the faces on the painting. (3) W.J.T. Mitchell addresses a similar aspect of this seduction pointed out by Seymour. He states:

“Art historians may know that the pictures they study are only material objects that have been marked with colors and shapes, but they frequently talk and act as if pictures had a feeling, will, consciousness, agency, and desire." (4)

He considers this entity that pictures possess as “aura,” which is related to the seduction that Seymour feels when he looks at the paintings by Frans Hals. According to Berger, this seduction is merely an illusion of the past, which Seymour cannot escape. He simply cannot stop himself from making assumptions based on his point of view on society and social relations. Berger describes mystification as the process of explaining what might otherwise be evident. (5) He describes the evidence of a picture as the fact that Hals painted the new characters and expressions created by capitalism and this was the first painting containing these aspects. (6) Someone, who had never seen these paintings before, may read the history behind the paintings in a completely different way and may have different assumptions. Therefore, according to Berger, one should avoid mystifying the past to find connections between the past and present. Only then, we can ask the right question of the past. (7)

Berger mentions the invention of the camera and how this new technology enabled us to experience the world, unlike any other person who lived before the emergence of the camera. It enhanced the world of reproductions. Since our eyes are like windows, opening to the world, or like a lighthouse and its beam, as Berger suggests, it has not been possible for us to see something without being there to see that thing before the invention of the camera. Now, we can experience what the cameras have captured as if its was seen by our own eyes. We do not have to be in the same place as the photographer to seen the image. Now, pictures come to homes, schools, public places and they act through different mediums. This relatively new invention gave rise to new questions, such as the questions: “What is authentic?”, “Does it matter to see the original rather than the reproduction?”, “Could the reproduction be more vivid than the original?”. The authenticity of an image has become more questionable and thas been replaced by he question of “meaning”. As Berger suggests, the meaning multiplies and is fragmented into many meanings. (8) Moreover, as Berger suggests, the camera destroyed the idea that images are timeless, (9) Paintings that were painted before the invention of the camera were always depicted from the view of the painter and we, as spectators, were obligated to see it from this prescribed angle. But now, these angles and the limited position of the spectators have changed. The painting reacted to this new development in the world of the images. Berger refers to Picasso’s “Still Life with Wicker Chair” and how it depicts all the angles of daily life as if it was captured by the camera. Thereby, it challenges the new concepts created by the camera.

The camera also abolished the connection of the paintings to the places of exhibition. Before, a painting could only be seen at he place, where it was displayed, and it could only be at one place at a time. However, nowadays, it is possible to digitally reproduce and represent it on an endless number of screens and prints. Its uniqueness has faded away, but its meaning has been multiplied. Berger says that, due to the camera, paintings come to the spectator rather than the spectator to the painting, and as it travels, its meaning is diversified. (10)

One might argue that an original artwork is still authentic and superior to a reproduction, but sometimes a reproduction might be so good that the original is scrutinized. Berger gives the example of the “Virgin of the Rocks” by Leonardo Da Vinci. (11)

For some, this painting is exhibited at the National Gallery in London, for others, it is shown at the Louvre Museum in Paris. Both paintings are exhibited as the authentic and original painting by da Vinci. However, one of them is a reproduction. Whereas one might be fond of the one in the National Gallery and be affected by its uniqueness, the other thinks the opposite – but still “feels” the same. Perhaps the reason for the interest in this painting is this whole ambiguity about the original. The National gallery sells more reproductions of “The Virgin and Child with St Anne and St John the Baptist” than of any other artworks in the gallery, since someone bought the original for 2 million pounds. (12) The painting is no longer interesting for its artistic value, but for its market value. Therefore, the reproduction can also feed those, who feel neglected when they cannot buy or see the original, and the market value of an artwork has always been the profit source for reproductions.

It is possible to alter the context of an image, by extracting parts of it. In addition to that one can change the meaning and affect the impact of an image by visually altering it. Yet, the artwork should be seen as a whole. Before the ear of reproduction, when a painting or an artwork was presented in a gallery or on a chapel wall, you could not look at a specific part of a painting. Now, reproduction also enables us to alter the images, by cutting parts from or adding parts to it. Berger gives the example of “Venus and Mars” by Sandro Botticelli.

When we inspect the painting as a whole, it is an allegorical painting depicted with mythological creatures. However, when we cut the face of the girl from the painting and just look at this part, it shows a portrait of a girl. The meaning has been altered by the transformation that the reproduction caused. (13)

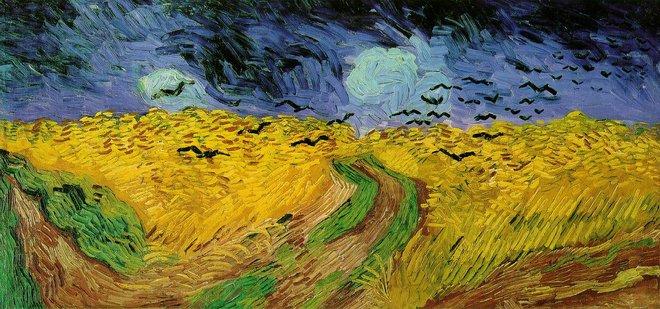

The same also applies to the painting Berger refers to. (14) When we take it as a whole, it tells a story or perhaps many stories at the same time, like a movie. However, a reproduction of it might change the meaning, by exempting and representing parts of the work. For example, in the first one, it is a painting of some crows with a gathering in the background. One may get the feeling of eventual death. While the last extracted part, the one with the windmill, could be seen as a joyful landscape painting.

Berger further argues that the addition of the sound represents another technique of reproduction to change the meaning of a work. (15) Paintings themselves are by nature silent objects. This is what makes them more striking. The stillness, the silent treatment they give to us when we look at them. However, the addition of sound or music might change the meaning and the experience of the painting.

Berger refers to Bruegel’s Procession, suggesting to look at the painting under different sonic circumstances, silent and with music. (16) The silent experience would be more striking, while the one with music depends on the kind of music playing in the background. In addition to music, various sound effects could be played to transform its meaning. Berger also mentions those pictures that come with words and how words can manipulate the way we look at images. (17)

In the example above we see a painting by Van Gogh. Alone, it is a pleasant, merely gloomy landscape painting of a wheat field. Everything changes when the sentence “This is the last painting painted by Van Gogh” appears underneath the image. Suddenly, our perception about the painting shifts, we become more emotional and less critical about it.

A relation to the aforementioned concepts and my own work can be made from different aspects. I also dealt with some sort of reproductions and ways of transforming them into my video artworks. For example, in an associative montage, I combined images and short videos from different sources.

When different images and videos are added to each other, they evoke different meanings. For example, the first image is the Atakule, symbol of Ankara, the guy shown afterward is the ruler of Ankara, therefore Turkey right now. The rabbit alone is just a bunny, running away from the predators. Yet, when it is combined with the city images and cops, it represents the people, feeling from the police. The girl in "Run Lola Run” is a girl, who is trapped in a looped timeline, where she experiences the same things over and over. No matter what she does, the consequences always are the same, or at least, she feels that way. As Berger explained, it is possible to transform the meaning of an image, by employing this method.

When discussing his arguments, Berger draws on concepts of Visual Culture Studies from the 1970s, when this field had just emerged. The theories and ideas he presents are still valuable today to understand the visual world surrounding us. However, a more recent analysis can be made by applying the concepts of this study to digital images.These days, we, as viewers, are even more involved than the people at the time, when Berger made his TV series “Ways of Seeing” and the respective book. People are living their lives with 8-10 screen hours per day. That is probably much more than the 1970s. In his TV series, Berger criticizes the restrictions of the TV format, pointing out the need for peer to peer experience, where people could reply to him. (18) In doing so, he successfully predicts social media tools such as YouTube, where the broadcaster can be in touch with the audience.

To conclude, Berger makes an introduction to Visual Studies in his own terms. He analyzes the concept of “mystification” and how we add different meanings to images by making assumptions about truth, beauty, civilization, etc. We, as human beings, who are surrounded by images, tend to make assumptions when we see them. Images are now different in terms of the way they are presented. We consume the reproductions more than the originals and it is possible to change the meaning of a painting with some reproductions methods such as cutting portions from it or adding, using sound and music, while presenting it or adding words around them. These methods do not only alter and alienate the meaning of images, they also divide them into different meanings.

Endnotes

(1) John Berger, Ways of Seeing (London: Penguin, 1972), 11.

(2) Ibid., 11.

(3) Seymour Slive, Frans Hals (London: Phaidon, 1970).

(4) W. J. T. Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want? (USA: The University of Chicago Press, 2005), 31.

(5) John Berger, Ways of Seeing, 16.

(6) Ibid., 16.

(7) Ibid., 16.

(8) Ibid., 19.

(9) Ibid., 18.

(10) Ibid., 20.

(11) Ibid., 20.

(12) Ibid., 23.

(13) Ibid., 25.

(14) Ibid., 26.

(15) Ibid., 31.

(16) Ibid., 31.

(17) Ibid. 27

(18) John Berger, Ways of Seeing, Episode 1 (BBC: 1972).

Bibliography

- Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin, 1972.

- Slive, Seymour. Frans Hals. London: Phaidon, 1970.

- Mitchell, W.J.T., What Do Pictures Want? Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005.