BAUHAUS.INSIGHTS: »The Gauforum in Weimar« – An Exhibition Everyone Should See

Many people pass this place daily without paying it much attention. To be fair, it does not look very inviting; enclosed within the huge and somewhat repelling building complex is an open space with underground car park entrances, and its sheer monumentality starkly contrasts with Weimar’s otherwise small-town charm. Nevertheless, the Gauforum is as much a part of the city’s history as Theaterplatz, Schillerhaus, and Frauenplan. So why do we know so little about it?

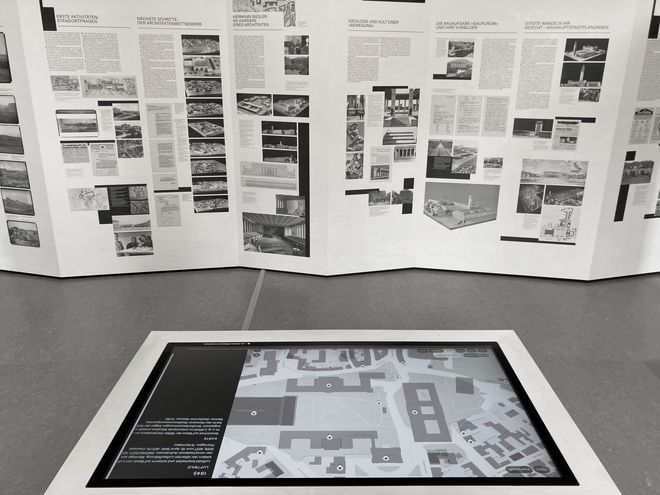

The exhibition »The Gauforum in Weimar – a Legacy of the Third Reich« lays bare the history of the never-completed monumental complex as a unique example of architecture representative of the National Socialist era. Using original photos and documents, accompanying texts and interactive before-and-after views, the tower construction reveals the reckless approach of the Nazis to urban planning.

Dr. Christiane Wolf, director of the Modernist Archive at the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, conceived and designed the exhibition as curator, together with Dr. Norbert Korrek and Dr. Justus Ulbricht. We asked her some questions about the history of its construction, how to deal with such an ideologically charged place in the present day, and what responsibilities arise from its history.

Dr. Wolf, the Gauforum in Weimar is one of the few surviving architectural complexes of the National Socialist era in Germany and is also a place of contradictions. As an expression of totalitarian power and National Socialist ideology, it was never completed. What were the contemporary functions of this place, and why was it built in Weimar of all places?

Indeed – why Weimar? From the beginning of the 20th century at the latest, Weimar was a focal point for right-wing conservative groups and individuals. This explains why, following the re-legalisation of the party, the first NSDAP party rally was held here. This had mainly to do with individuals such as Baldur von Schirach, Reichsjugendführer (National Youth Leader) in the Hitler Youth, and Fritz Sauckel, at that time Reichsstadthalter (Reich Governor) and later Gauleiter (Regional Leader). Hitler was at that time seeking locations to give speeches and make public appearances; his imprisonment in 1926 meant he was only allowed to speak publicly in Weimar and Braunschweig. He was prohibited from giving speeches anywhere else. He also wanted to create a new German national identity. Weimar, as the founding place of the Weimar Republic, was an obvious choice – also to reclaim this place. And to also construct the German geographical-cultural »centre«. People had been trying even since 1900 to pinpoint the cultural centre of the German Reich, the German nation. This eventually led to Thuringia as the heart of German culture. This is why Hitler came to Weimar at such an early point. He arrived in civilian clothes and stayed at the Hotel Elephant. By the end of the National Socialist era, he had visited Weimar more than forty times – because, as he wrote, he loved the city.

Back to the Forum. The federal states have existed in a similar form since the 1920s. Their replacement begins in 1933 with the establishment of so-called »Gaue«. Each Gau is to have its own representative architectural centre of power. Thuringia and Weimar play a major role. This is because in 1930, the NSDAP was represented in the government of Thuringia for the first time. And Fritz Sauckel, a long-time companion of Hitler, is made Gauleiter in 1933. Sauckel wants Weimar to become a centre of power – and this is achieved with the Gauforum. Weimar is the first place where Hitler personally intervenes in support of planning and building such a complex.

The area chosen for the complex, which today is situated between the old town and the railway station, is convenient in terms of accessibility. This is of great importance because such marches were expected to attract well over 10,000 or even 30,000 attendees requiring transportation there and back. Hence the importance of the proximity to the railway station; motorways did not yet exist at the time of the competition. According to Hitler, the old town was not to be affected. This site was selected via a procedure carried out by then director of the Architecture and Building Arts Academy, Paul Schultze-Naumburg.

Plans were made for an administrative building for Gau leadership, a building for branches of the NSDAP – i.e., the »League of German Girls«, the »Hitler Youth« and the »German Labour Front« – and the Reich parliamentary building, the seat of the Gauleiter. Although there were no plans for a hall at that time, there was a large parade ground as well as a tower that was to form the silhouette. A large hall was then added during the competition procedure and planning process. The tower was gradually made taller until it was two-thirds higher than it is today, crowned by a globe with a set of bells. It was intended to take on pseudo-religious functions, and you could certainly say there was an element of new religiosity to National Socialism. The regime built its own »cathedrals« for the so-called Volksgemeinschaft (national community), featuring sacred symbols such as organs and crypts. National community meant loyalty to the party, obedience and the exclusion of anyone not belonging to the community.

The exhibition describes how an entire neighbourhood was razed to make way for the construction, including a green space and park along the Asbach river and over 150 residential and commercial buildings in the Jakobsvorstadt district. How should we imagine this historically developed neighbourhood that Weimar lost as a result of this action?

Weimar was one of the first cities to receive a large park as part of its urban expansion. The land there sloped steeply, much more so than we see today, and the green corridor – starting at Wimaria Stadium, passing the swimming pool, continuing to the power station and ending at Tiefurter Park – formed Weimar’s green lung. The city lies in a basin and needed the ventilation, which is why the area was never built on. Today, such ventilation is missing in this location.

To build the Gauforum, extensive expropriation measures were initially carried out at the site. The expropriated and demolished buildings were Wilhelminian-era houses, some of them detached. Towards the Jakobskirche, there were mainly craftsmen’s businesses and workers’ lodgings. The residents were to be given replacement premises, which can still be seen today in Freiligrathstraße. These are 1930s-era buildings, designed by a university lecturer and his students from the former Weimar University. This was how the Nazis imagined an ideal artisan town: a historicised, medieval ideal.

You curated the exhibition together with Dr. Norbert Korrek and Dr. Justus H. Ulbricht, researching and preparing the content. The photos show lots of Weimar’s residents lining the parades of the National Socialist leaders, cheering. How difficult was it to find original documents and sources, and how did you feel personally about delving so deeply into Weimar during the Nazi era?

I completed my doctorate on the Gauforums and during the process of the research I visited city and state archives as well as the Federal Archives. Preliminary work and research on the topic was also conducted by Dr. Norbert Korrek from the Theory of Architecture Professorship. The sources are excellent and well documented. There was material in magazines and film productions created by the Nazis, for example. We visited countless archives and also looked at private items.

The Gauforum in Weimar was a showcase project that was widely reported on and even led to an exhibition in Madrid in the 1940s. In that respect, finding material wasn’t difficult – otherwise we wouldn’t have been able to put the exhibition together in a year and a half. And we had great support here in Weimar from the state archives – now called the Thuringia State Archives – as well as the Weimar City Archives and our City Museum, which very quickly provided us with photographic material. It was an excellent collaboration. And the Zeitsprung media installation by Alexander Rutz, which included the before-and-after pictures, also entailed a lot of individual research work.

How does it feel to delve so deeply into the Nazi era? I get that question a lot. Given the subject of my doctorate, I already had some experience with that before coming to Weimar. I sought help and developed methods to separate the images and sources from my personal life. I also don’t think it can be compared with memorial work. But I found it difficult to distance myself from the inhuman language. I also found it extremely difficult to research in the state archives the use of forced labourers and prisoners from the Buchenwald concentration camp. It requires reading through long lists of orders placed by businesses for »human material«, from the master baker in Weimar all the way to IG Farben. Just thinking about it still sends chills down my spine. It wasn’t easy to separate that from myself and my everyday life. But I think it always makes sense to practise any method you can to help distance yourself from the content.

There was a long struggle after 1990 concerning how the site could be reused. What role was played or is still played by members of the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar with regard to appropriate use of the site of the former Gauforum and the Quarter of Weimar Modernism that subsequently emerged?

The site was divided after 1990. The hall was placed under the administration of the Thuringian Liegenschaftsverwaltung (property management agency) since it had been largely financed by Adolf Hitler himself. The other buildings immediately became the property of the state of Thuringia. The university took up this issue more or less immediately after 1990. Two Bauhaus colloquia took place in the early 90s, one on power and architecture and the other on totalitarianism. In the context of these colloquia, the Gauforum plays a role in the overall context of the Nazi legacy. In the Theory of Architecture Professorship, Karina Los wrote a doctoral thesis that proposed placing a building on the large square so as to break it up and equip it with a new information system. Dismantling it down to its skeleton, i.e. the reinforced concrete rib construction, was also considered.

The Theory of Architecture professor played a major role here; it was also she who launched a project together with the state to install an exhibition at the historic site in the context of Weimar being chosen as the European Capital of Culture in 1999. I was already involved in the subject at that time. I wrote a dissertation at the Ruhr University Bochum on the Gauforums as Nazi centres of power. In this context I also gave lectures in Weimar and was in close contact with Norbert Korrek. I then started here in the Theory of Architecture Professorship in January 1998 with the aim of collaborating with Norbert Korrek to develop and install an exhibition in the Gauforum.

In the meantime, there were starkly differing proposals on how to deal with the Gauforum complex, for example from urban initiatives. Kunstfest Weimar used the site in 2004, and Udo Lindenberg offered to use the hall as a permanent cultural venue. Unfortunately, the state wasn’t interested in co-financing this idea, so now we have a shopping mall.

In close cooperation with the city, which sponsors the Gauforum exhibition, and the Thuringian State Administration Office, which provides the space, the exhibition was then installed in the foyer of the so-called Turmhaus in 1999. It was renovated twice because we absolutely wanted to ensure the tower remained accessible. It would be unacceptable for me to move this exhibition to another location. It must remain in this historically poignant location and integrate the tower as a historical relic. From the outside, we see only a rectangular tower without any decoration. Inside, however, we see a sacred building intended for flags and banners, illumination during parades and rallies – pure aestheticisation, indeed the Nazi cult in its entirety.

What I still can’t accept to this day is that the square remains cordoned off and entry isn’t permitted. As a historian, I’m convinced that the park and later the square were taken away from urban society and never given back. Now it’s a so-called non-place, and I don’t think that’s right.

As you mention, the parade ground today is no longer accessible – but the historical significance of the place is still palpable. What would you like to see in terms of how the Gauforum is dealt with in future – by the city, by the University and by the next generations?

I think we have a good starting point with the so-called Quarter of Weimar Modernism. Since the Bauhaus Museum was built, we have at least had an extension of the square. Then there’s our modest exhibition, although it could be more effectively signposted. And since last year, one wing of the old complex has housed the Museum of Forced Labour. This is a good collaboration, and it already makes much more out of this place. But I would like to see the Gauforum signposted throughout the city and promoted as a place that is also part of Weimar.

And as I already said, I would like to see the square made accessible. Even if we can’t turn the shopping mall back into a cultural venue, we can give the square back to the city community and society; it’s something they lost when the Gauforum was constructed and never got back.

Dr. Wolf, thank you for this insightful conversation!

The questions asked by BAUHAUS.INSIGHTS were prepared by Press Spokesperson Claudia Weinreich.

Exhibition »The Gauforum in Weimar – a Legacy of the Third Reich«

Tower Building of the Gauforum

Jorge-Semprún-Platz 2

99423 Weimar

Opening hours: Tues-Sun 11 am to 4:30 pm

A digital version of the exhibition content can be accessed under https://www.gauforum.de