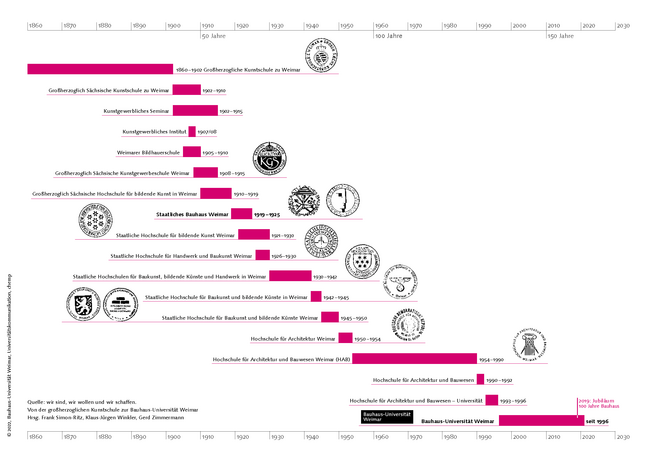

1860 »Großherzogliche Kunstschule« (Grand Ducal Art School)

The formation of the »Kunstschule« came about through a long-sighted developmental strategy for the Grand Duchy: After the intellectual golden age in Weimar had passed, a new cultural significance should be recovered through the cultivation of art and music education.

The Weimar School became one of the leading art schools in Germany during the 19th century. The school became part of art history under the heading »Weimarer Malerschule« (Weimar School of Artists). Students came from all parts of Germany and from around the world, among them were Max Liebermann and Max Beckmann. Despite the dependency upon the Grand Duke and the conservative attitude of the authorities, a progress teaching and learning concept prevailed. So much so that the students were able to select their professors.

In 1910 the »Kunstschule« was revaluated as the »Großherzoglich Sächsischen Hochschule für bildende Kunst« (Grand Ducal Saxon College of Fine Arts) in Weimar. The painter Fritz Mackensen, a committed and reform-oriented, who later became a significant Nazi-activist, took on the role of the director.

1908 »Großherzogliche Kunstgewerbeschule Weimar« (Grand Ducal Vocational Arts School)

Since the 1860s there had been efforts within the Grand Duchy to connect trade and industry with the arts. Henry van de Velde, an internationally renowned designer and reformer, was appointed in 1902 for this purpose. Van de Velde set up a vocational art seminar that was succeeded in 1908 by the »Großherzogliche Kunstgewerbeschule« (Grand Ducal Vocational Arts School), which he directed until its closure in 1915. The school attended to the products created by the Thuringian craftsmen and industry and became an early modernist laboratory. The Vocational Art School's faculty was composed of individuals from various countries. Work of the »Kunstgewerbeschule« suffered, however, due to a lack of institutional and financial recognition from the Grand Duchy. Professional competitors and conservative citizens in Weimar also antagonised van de Velde.

In 1905 and 1906 the building of the »Kunstgewerbeschule« was erected, which today houses the Faculty of Art and Design, according to van de Velde's plans. During this time he was commissioned to create a new building for the College of Fine Arts. The building was completed in 1911. Today it is the Main Building of the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar.

1919 »Staatliches Bauhaus Weimar« (unification of the former Grand Ducal College of Fine Arts and the former Grand Ducal Vocational Arts School)

The founding of the Bauhaus within the building of the former »Kunstschule« was a result and an expression of the socio-political upheaval present in Germany after the fall of the »Kaiserreich«. Weimar was the central location of this upheaval: During this time the national assembly founded the first German parliamentary republic just a few streets away.

The appointment of Walter Gropius as founding director was preceded by a long and lively discussion about how design could be revolutionised so that the potential of the continually advancing industrialisation could be utilised in order to optimise the production of everyday goods and architecture through innovative artistic work. Gropius had already created such a plan back in 1916; he brought with him experience with advanced industrial construction and a familiarity with large industrial mass production of consumer goods. This corresponded well to the programme envisaged by the coalition of the Social Democratic Party, Centre Party and the German Democratic Party: to establish a social state in accordance with the development of modern industry. In the newly formed state of Thuringia, the Bauhaus was supported by these three parties and the Communist Party of Germany.

The didactic concept included a foundational artistic education with Paul Klee, Lionel Feininger, László Moholy-Nagy, Wassily Kandinsky and Oskar Schlemmer. They shaped the character of art in the 20th century. They were also a fairly international group for that period in time and they revolutionised conventional academic precepts.

Well-known students of this time included the product designer Wilhelm Wagenfeld as well as the weaver Gunta Stölzl. In the beginning about half of the students were female, but between 1924 - 1925 females made up only a third of the student body. Among the instructors, female remained a tiny minority.

Post-war conditions initially led to a strengthened cooperation with the skilled crafts and trade. The products created in the workshops (bookbinding, stage, graphic printing, stained glass, wood carving, stone carving, metal, carpentry, ceramics, mural art, weaving) also contributed to the support of the Bauhaus, since state funding was very scarce during this time despite the sympathetic government. The plan was to create a close cooperation with the industry in order to design commercially attractive prototypes for mass production.

In 1923 the Bauhaus organised an acclaimed industrial exhibition. It was for this purpose that the Haus am Horn was created. Haus am Horn is an experimental building that includes contributions from all of the workshops and was the first – and only – constructional product of the Bauhaus in Weimar. It was constructed under the leadership of Georg Muche.

The Bauhaus was faced with many challenges. The activities of the new generation of artists provoked the more traditionally oriented professors. These professors decided to resign and founded the Hochschule für bildende Kunst (College of Fine Arts) in 1921. By transferring to industrial production in 1923, there was an increased amount of rejection from the skilled crafts and trade. This rejection reverberated within the right-winged and pronounced nationalistic parties. When these right-winged parties won the majority in Thuringia in 1924, the Bauhaus was forced to leave Weimar and move to Dessau.

1926 »Staatliche Hochschule für Handwerk und Baukunst« (State Academy of Crafts and Architecture)

Under the direction of the architect Otto Bartning, who in 1918 was one of the master-minds behind the foundation of the Bauhaus, the university offered a conventional architectural education for the first time in Weimar as well as the continuation of the artisan workshops that followed the industrial form design trends. The »Hochschule für bildende Kunst« (College of Fine Arts) existed at the same time as its own institution but it had already become decreasingly important.

In addition to Bartning, there were other prominent individuals who had a global impact on the shape of architecture and urban design in the 20th century. Ernst Neufert became the director of the architecture faculty in 1926 and managed the »offene Bauatelier« (open constructional atelier) together with Bartning. Neufert specialised in the rationalisation of construction management and reformed the dissemination of technical information. He later worked on behalf of Albert Speer for the Nazi regime and became a professor in Darmstadt in 1952.

Cornelis van Eesteren began teaching urban design in Weimar in 1927. He was the chairman of the Congrès International d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM) from 1930 to 1947 and thus a central figure of international modernity. With the arrival of the civil engineer Max Mayer, the university gained a powerful advocate for effective technical and economical rationalisation along the lines of Fordism.

1930 »Staatliche Hochschulen für Baukunst, bildende Künste und Handwerk in Weimar« (State Academy of Architecture, Fine Arts and Crafts in Weimar)

When the Nazi Party won the majority in Thuringia, the former reformist Paul Schultze-Naumburg, who had now become a race ideologist, was appointed director of the »Vereinigten Kunstlehranstalten« (United Arts Academy) in Weimar in 1930. According to the motto »strengthen the craftsmanship«, education was radically transformed. The curriculum was to be adjusted to follow in line with »Nazi tendencies and thought«. Under the banner »Schutzes der Heimat« (protection of the homeland), everything supposedly foreign and international was denounced as essentially different in nature.

According to these conditions, only three of the 32 instructors were kept on staff at the new school.

On 10 November 1930, the opening of the »Hochschulen für Baukunst, bildende Künste und Handwerk« took place under the swastika flag. Prior to the opening of the school, the buildings were »cleansed« in October 1930 and the murals by Oscar Schlemmer in the former workshop buildings were whitewashed.

In stark contrast to the concept of modernity, Schultze-Naumburg directed the school according to the values dictated by »Blood and Soil« ideology, which among other things focused the design education on Goethe's garden house as a supposed prototype of »German architectural thinking«.

1946 »Hochschule für Baukunst und Bildende Künste« (Academy of Architecture and Fine Arts)

Following the end of the war, academic life took place outside of the campus buildings, which were now occupied by US troops. The main focus at this time was on the plans for the reconstruction of Thuringia.

In October 1946 the university was able to begin once again, this time with two departments: Architecture and Fine Arts. During the soviet occupation, the director Hermann Henselmann tried in vain to form a connection between the educational institution and the tradition of the Bauhaus. He was, however, successful in bringing former »Bauhäusler« back to Weimar such as Gustav Hassenpflug (urban design), Rudolf Ortner (Werklehre) and Peter Keler (Vorlehre) and was able to establish the Fine Arts as its own educational course . In 1949, Henselmann left the university and went to the »Bauakademie« in Berlin.

When the ministry took over the construction of the university in 1950, a technical restructuring began that was in line with the industrially oriented development strategy of the newly founded German Democratic Republic (GDR). Partisanship was enforced administratively. In 1951 the Fine Arts department was closed in conformation of these ideologies. Many professors and students left the university and headed west, among them was Gustav Hassenpflug, Werner Harting, Hardt-Waltherr Hämer, Herbert Kirchberger, Hans von Breek and Mac Zimmermann.

This transition towards a technically oriented institution became more apparent in 1950 when the university was renamed as »Hochschule für Architektur« (Architecture Academy). Under the leadership of the civil engineer Friedrich August Finger, the university developed into an institution that performed the highest level of material inspection and also became involved in the area of building material development.

1954 »Hochschule für Architektur und Bauwesen« (University of Architecture and Civil Engineering)

In 1954 further adjustments were made to fit the developmental strategies of the GDR: due to the accelerated speed of industrialisation, civil engineering took on a central role at the university. In addition to the Faculty of Architecture, the Faculty of Civil Engineering as well as the Faculty of Materials Science and Materials Technology were established. From that point on – and until 1996 – the institution was called the »Hochschule für Architektur und Bauwesen Weimar« (HAB). Through the construction of new buildings and the acquisition of existing facilities, the HAB became a prominent institution for urban design in Weimar.

In 1968, the focus on structural engineering was expanded and a study course in Spatial Planning was introduced. During this time, the first planning degree programme was also established in Dortmund in West Germany. The new orientation manifested itself in five sections (faculties): architecture, civil engineering, building materials process engineering, computer engineering and data processing, as well as regional and urban planning.

Despite the primacy of partisanship, the »Hochschule für Architektur und Bauwesen« (HAB) Weimar was able to establish a wide international network and receive recognition as a scientific university. It also became a centre for intellectual debate within the GDR. Throughout the 1980s, a core of reform-minded professionals developed out of a comprehensive criticism of the spatial development models of the GDR and this led to the re-establishment of the Bauhaus Dessau in 1987.

To this day the history of political repression at the university has not yet been written.

1990/1991 Restructuring of the Faculties*

With the political turnaround and under the rector Hans-Ulrich Mönnig (1989-1992), a process of restructuring began which was oriented around the requirements of a cosmopolitan university. The section structure was abandoned and the faculties restructured: urban planning and regional planning were combined with architecture, while building materials components was integrated into the Faculty of Civil Engineering. When Gerd Zimmermann became rector, the Faculty of Art and Design was inaugurated in the winter semester of 1993/94, with the result that a wide range of courses could be offered, from fine art to design, visual communication, architecture and urban planning, civil engineering and computer studies; the college became a university of »Building and Design«.

1995/1996 »Bauhaus-Universität Weimar«*

Walter Gropius’ much quoted statement about the »unity of art and technology« was given a new meaning through the expansion of the study courses on offer. The university aimed to complement its engineering with art courses, not art or technology, but art and technology – a unique concept which a classical school of engineering or art would be unable to offer. This new modern and future-orientated profile was taken into account in the decision by the Council in October 1995 to change the name to Bauhaus-Universität Weimar.

The official renaming was celebrated one year later.

In autumn 1996, consistent with the art-technical thrust of the university, the Faculty of Media was set up and today covers the whole range of possible studies, with courses in the sectors media culture, media management, media design and media systems (media informatics).

2001 Reformed Study Courses – Internationalisation*

In keeping with the Bologna Process, the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar introduced study courses towards a Bachelor’s and a Master’s Degree – initially in Building Management and Infrastructure & Environment at the Faculty of Civil Engineering. One year later, the Civil Engineering study course followed suit. In autumn 2003 the Faculty of Media also adapted its study courses. The conversion to the new system was completed by the end of 2009.

2015 The Bauhaus-Universität Weimar today and in the future*

Today the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, with its four faculties of Architecture and Urbanism, Civil Engineering, Art and Design and Media, has a very special profile and offers a range of nearly 40 study courses that are unique in Germany; from fine arts and product design to media design and media culture, architecture and civil engineering environmental science and project management. Currently there are 4,000 students enrolled at the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, including about 450 foreign students.

Indebted to Humboldt’s ideal of a unity between university research and teaching, the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar has defined four research focal points and four art-design core areas, in addition to its traditional working sectors. The research focal points are: cultural-scientific media research; digital engineering; urban, infrastructure and space research, and materials and constructions. In the art-design core areas special attention is given to film and the moving image, art in the public domain, product design and the training of architects in general.

2019 Centenary »100 Years of Bauhaus«

100 years of Bauhaus: For the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, the centenary offers an opportunity to learn and work together. It is an invitation to seek and put forward solutions to contemporary questions in research and art, teaching and study, and offers impetus for a constant new beginning, for ventures into the unknown – similar to the Bauhaus of 1919.

The Bauhaus Centenary programme provided guests with the opportunity to get to know the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar in numerous different ways. A great number of instructors, students and alumni participated in creating the programme and organising exhibitions, conferences, lecture series, concerts, festivals and much more.

* Please note that the marked sections are currently being revised.